From India to the Caribbean and Other Far Far Lands: The Journey of Indentured Indians and the Legacy They Carry

When slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1833, colonial plantation economies—particularly those built on sugarcane, cotton, and cocoa—suddenly faced a labor crisis. Fields in the Caribbean, Mauritius, Fiji, and Africa were vast, but hands to till them were few. And so began one of the most far-reaching and understudied migrations in modern history: the movement of over a million Indians, mostly from the present-day states of Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh, to distant lands as indentured laborers.

The Recruitment: A Promise Far from the Truth

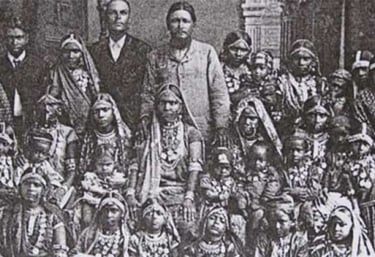

Between 1834 and 1920, Indian men and women were recruited to work overseas on contracts that promised decent wages, free passage, and the prospect of returning home after five years. But the reality was far from romantic. Recruiters, known as arkatis, roamed the villages of North India, often preying on the desperate—those affected by famine, debt, caste oppression, or the disintegration of traditional rural economies under colonial policies.

For many, the journey began in places like the port town of Kolkata or Chennai, where thousands were held in depots before being shipped to British, Dutch, and French colonies.

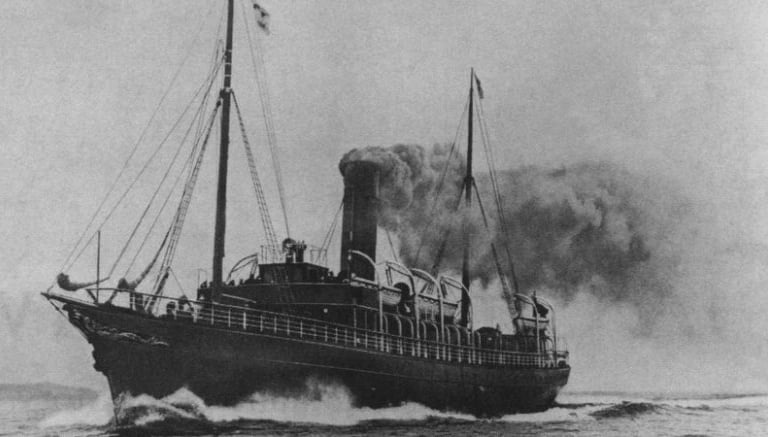

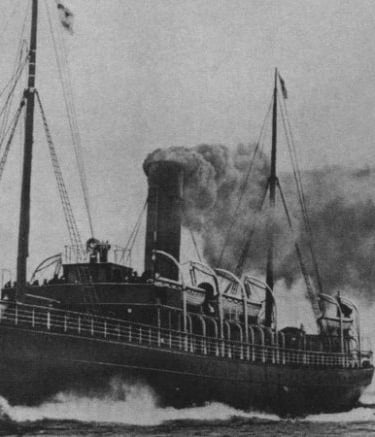

The Middle Passage, Reimagined

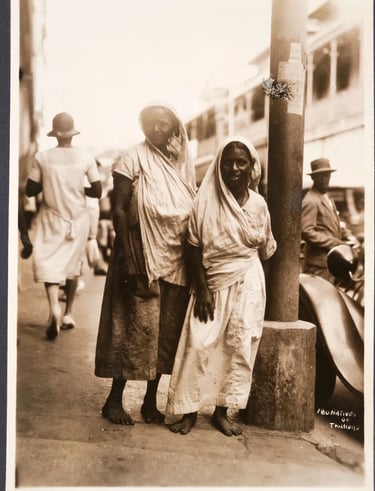

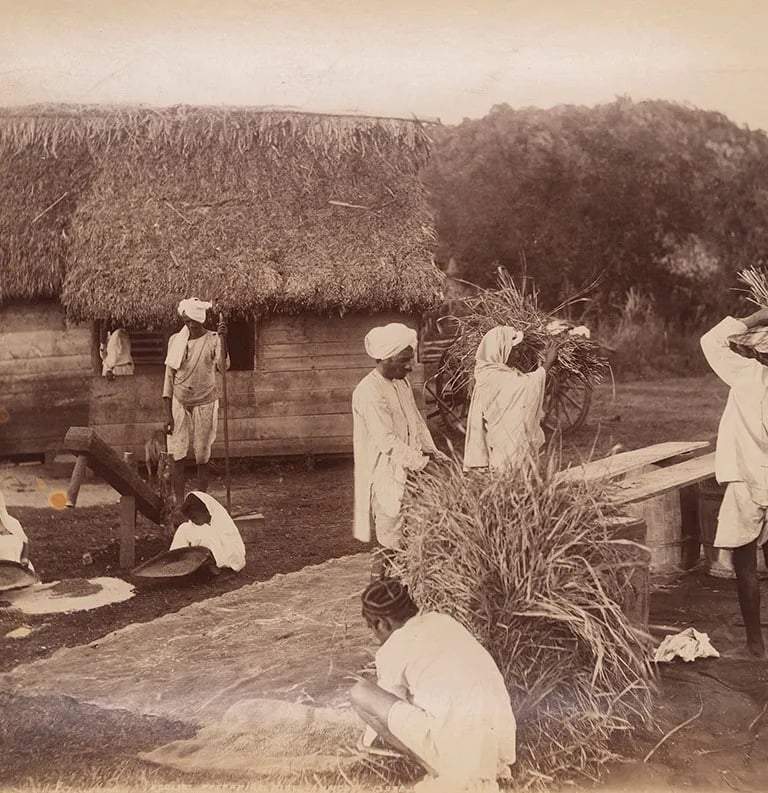

The voyages were long—sometimes three months at sea—and conditions aboard the ships were difficult, though not as brutal as the slave ships that preceded them. Still, disease, cramped quarters, and uncertainty haunted the journey. Upon arrival in faraway lands—Trinidad, Guyana, Suriname, Fiji, South Africa, Kenya, Mauritius, Réunion—the migrants were assigned to plantations where they would work long hours for meager wages, often under harsh supervision.

Indenture or Injustice?

Though indenture was not slavery, it came uncomfortably close. Workers were bound to one employer, prohibited from leaving without permission, and often punished with jail terms for minor offenses like desertion or disobedience. Women were a small percentage of the migrants—roughly 25%—and many faced gendered violence, forced marriages, and the burden of preserving cultural and emotional continuity.

And yet, within these constraints, a unique kind of resistance and resilience emerged.

Building Lives, Preserving Culture

When their contracts ended, many Indians chose to stay. Returning to India was difficult, both financially and emotionally. The "kala pani" (black water) crossing had marked them as outsiders back home. And so, they began to plant new roots.

Temples and mosques were built, Bhojpuri and Tamil songs were sung, pholourie and roti were served alongside cassava and plantain, and Ramayan readings were conducted under palm-thatched roofs in Guyana and Fiji. Over generations, Indian-origin families fused their ancestral traditions with local identities to create something entirely their own.

From Cane Fields to Parliament

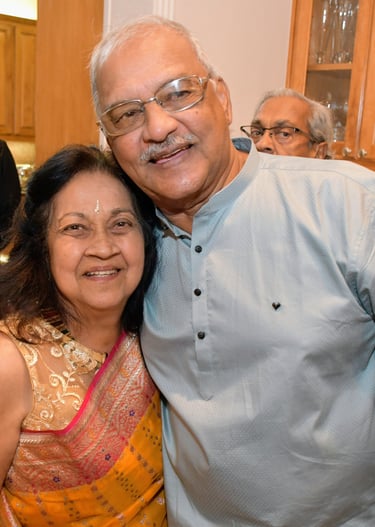

Today, the descendants of these indentured migrants—often called Girmityas (from the word “agreement”)—form vibrant communities in their respective nations.

In Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, and Suriname, people of Indian origin have served as presidents, prime ministers, and cultural icons. In Fiji, despite political upheavals and ethnic tensions, Indo-Fijians have held sway in commerce, academia, and the arts. In South Africa and Mauritius, Indian heritage continues to shape language, cuisine, and public life.

But their journey has not been without pain. In many countries, Indo-descendants have faced racial marginalization, forced assimilation, and exclusion from land ownership or political participation. And yet, they have persisted—with poetry, prayer, protest, and perseverance.

Reconnecting with the Motherland

In recent decades, as travel and technology have collapsed distance, many members of the Indian diaspora have sought to reconnect with their ancestral roots. Pilgrimages to India, Bhojpuri revival festivals, DNA testing, and cultural exchange programs are building a new bridge across time and ocean.

Organizations like Global Bidesia are working to create these links—not merely to preserve heritage but to celebrate it, to ensure that the journey of the Girmityas is remembered not as a footnote in colonial history but as a living, breathing legacy.

From Servitude to Sovereignty of Spirit

The story of indentured Indians is not just about ships and contracts. It is about humanity’s will to survive, adapt, and thrive. It is about a people torn from their homeland who managed to transplant its soul into foreign soil—and watched it blossom.

They may have arrived as servants, but today, they stand tall as citizens, leaders, artists, and cultural torchbearers. Their story is not just Indian. It is Caribbean. It is African. It is Oceanic. It is global.

It is a story worth telling—again and again.